As we mourned the loss of those precious minutes, the warmth leaked from the air. It grew chilly and then cold. T-shirts and shorts turned into light sweaters and long pants, then an insulated jacket, long underwear and joggers. Eventually, my sheepskin gloves came out. Finally, a balaclava joined the ensemble.

The winds stirred and strengthened. The clouds, thicker and more robust in the weightier air, betrayed the wind's breath as exhaling largely out of the west. The face of the Ottawa river deepened from blue to grey. The Gatineau Hills slowly aged from green to a breathtaking mosaic of every conceivable hue of brown, red, yellow and orange. And then one day, there were no leaves at all - only naked trees standing sentry on the muddled brown face of the hills. In some places, pines defiantly retained their verdant cloaks and, rustling in the late autumn wind, mocked their defrocked neighbours.

The face of the earth had changed. This aging, this thinning of the surface, exposed elements I'd never seen before...or, if I had, I'd forgotten about them if I'd paid them any attention at all. Here - a rocky outcropping springs from the side of a hill and plunges down its face like a silvery waterfall frozen in time. And there - an old yellow school bus, tinged in rust, inexplicably sits in the middle of a stand of trees a good mile away from the nearest road or trail.

In some ways, the progression of summer into fall into early winter reminded me of the passing of a loved one.

Strong and vibrant for so long and then with time - slower, older, withdrawn.

Sickness or old age sets in and visits are shorter, dominated by recollections of the earlier days when strength, time and possibilities were in abundance; sad smiles cross thinning lips, crease skin like leather.

And then one day, they're gone; just an impression on the couch, an empty seat at the table, a bed stripped of linens, a half-glass of water and smudged reading glasses on the bedside table.

It made me feel sad.

The Smith, however, took what I saw as a slow, bittersweet death and turned it into a rebirth.

Invigorated by the cooler, denser air, she leapt into the sky and climbed like a homesick angel. The engine, while perfectly faithful over its 40 year life, sounded like it had rolled off the assembly line at Williamsport the week before. The fat, stubby wings cleaved the thick air with renewed vigour and buoyed plane and pilot aloft on the rising tide of the autumn air.

|

| The author's self-portrait of fall flying. (Author's collection) |

While the Smith was content to keep climbing to her service ceiling and very likely beyond, I almost always pulled up on the reins around 2000 feet. The main reason was the cold. The loss of just a degree or two at altitude made a shockingly painful difference. With shoulders hunched and elbows drawn tight against my body, I cowered behind my goggles and relished the heat from my breath pooling beneath the ski-mask drawn over my nose. The Lycoming's roar eventually subsided into a dull, monotonous hum behind the tinny ringing in my ears. While I was laid bare to the elements in my open cockpit, the blast of the propeller and the weight of the air rushing past created something of a capsule against the outside world. Eerily silent, life rushed by at 100 miles per hour.

The secondary reason was our collective size. At not quite 16 feet long and 18 feet wide, the Smith lived up to its moniker. I'd taken the Miniplane up to almost 4000 feet a few times and it felt as though we were in orbit. At that height, peering tentatively over the side had a dizzying effect. And it was lonely, humbling and, at times, frightening. The experience, more than any other in my life, swiftly brought to bear my insignificance.

The Smith remained aloof. After all, she'd been to Oshkosh twice, crossed half the continent and even vaulted the Northumberland Strait at the same height that made me nervous.

Despite her silent chiding, we had made huge progress during our first season together. I was still scared of the airplane, yes, but the sentiment had dulled from wide-eyed terror to fearful respect. There was still much handwringing prior to each flight. I routinely spent twenty minutes (or more) standing outside the hangar, rocking gently from foot to foot, watching each of the three windsocks in the same way a surfer gauges the waves before paddling out beyond the break. On some days, having rolled up the doors, pulled out the Decathlon, prepared the Smith and made ready for flight, I would sigh, nod resolutely and do everything again - in reverse.

"A plane isn't a car," my dad had said to me once, a long time before I'd started flying. "You can't just pull over if something goes wrong."

It was true. Best case scenario, you had to find an airport or field to land in as soon as practical; worst case, you had to put it down in whatever clearing the outside world afforded you in your moment of need.

Once I started flying and frequenting airports as the owner of a crisp, new pilot's license, another quote was unapologetically drilled into my head.

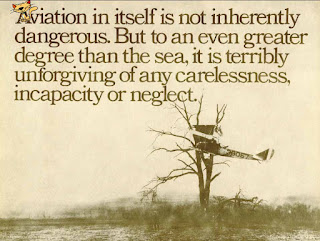

"Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect."

The quote, attributed to a Captain A.G. Lamplugh and 1930s London, was widely reproduced on aviation posters and it was a virtual certainty that one of those publications hung somewhere in your local airport crew room, dispatch area or classroom.

In my case, it lived on a square foot of yellowing melamine board hanging above the toilet at the flying school where I did my night rating, commercial license and aerobatic training. Every time I took a piss, I read that quote and took in the image of a burned out Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" biplane hanging in a blackened oak tree. Only the airplane's rear fuselage and tail remained. The tree, standing out darkly against the misty expanse of what I assumed to be the airport property, appeared to be the only obstacle for miles.

|

| The "Jenny" poster. (Image courtesy check-six.com) |

Every time I looked at that poster, I thought of those two guys and asked myself "why?"

In an effort to not end up like the two chaps in the tree, I approached each flight - not just in the Smith but any flight - as an evolving dialogue in self-awareness.

Am I ready? Am I safe? Am I prepared? Am I able to handle what may come? Do I have a way out?

If the answer to any of those questions was "no", I went home, poured myself a drink and toasted Captain Lamplugh.

|

| Taxiing in from the last flight of 2014. (Author's collection) |

And so, our first season unfolded tentatively and even then in the most conservative fashion. By the time of our last flight on Tuesday November 11th, 2014, we had logged a little more than 22 hours and each minute that been an investment and a learning experience.

The last flight was brief and meant only to warm the oil enough so that it would be easier to drain from the engine. I took the biplane out to the other side of Orleans, circled JP's farm twice and then returned to Rockcliffe. My landing was perhaps our nicest of the season and, as I taxied back to the hangar, I marvelled at what I took to be the Smith's grace. It made sense that the little ship, knowing her pilot had barely hung on all season, would help put that kind of exclamation mark on the year.

|

| Plane and pilot at the close of the 2014 season. (Author's collection) |

When we arrived at the hangar, my best friend was waiting to give me a hand with the work. We drained the Smith's oil and replaced it with 5 litres of preservation oil for her winter hibernation. We carried out some minor corrosion prevention work and removed the battery. We worked in silence; our labour - a solemn veneration to the passing of the season.

It was dusk by the time we had her back together and tucked into the corner of the hangar. The Decathlon followed suit. I let Seamus out by the side gate before rolling down the doors and tying them up.

|

| Preparing the Smith for winter storage. (Author's collection) |

A peaceful silence covered the field like a blanket as I padded back to the clubhouse. It only took me a few steps to realize that the only sounds I could hear were my breath and the soft scraping of my boots on the crumbling pavement. Anyone who has spent any time at an airport will tell you that these are rare moments. Airports, particularly small community fields like Rockcliffe, have a unique soundtrack: windsocks rustling, engines coughing to life before settling into a rhythmic purr, the clang of a wrench, a backfire, the rattle caused by a youngster hanging off the perimeter fence, muttered curses and happy greetings shouted across the ramp...

And yet, tonight...none of that, not a whisper, not a breath besides my own.

I would have stopped to experience this rarity fully but it was cold. The blanket of darkness had been pulled tighter around the field so that only the last belt of daylight shone through along its edges. On this night, this dying blast of sunlight was a shimmering ochre tinged in auburn and purple. It lasted for some thirty seconds, with only the raked tail of a small Cessna (a 150 or 152) by the fuel pumps breaking its dominance of the horizon. When it sank below the far horizon, only the lights of the clubhouse guided me.

The clubhouse was nearly empty. The dispatcher was working behind the desk, updating aircraft journey logs chronicling a busy day of flying. We chatted idly as I rummaged through the cash box looking for one of my instructing paycheques. Two men, who I assumed to be the pilot and passenger of the Cessna sitting outside, were loitering by the rack of snacks the club offered for sale.

"Everything's a dollar?" one asked. He had a pair of aviator sunglasses pushed up onto his forehead.

"Yep," I replied, scribbling down the particulars of today's flight and oil change in the Smith's journey log.

"I'll take a Snickers."

"Help yourself."

I snapped the log shut, dug my car keys out of my mail box and, saying goodnight to the dispatcher and nodding to the Cessna crew, stepped out into the November night.

When I arrived at work very early the next morning, my email inbox was flooded with messages about a small plane crash in Algonquin Park. The aircraft, a Cessna 150 on its way from Rockcliffe to Buttonville with two people on board, had made a mayday call around 8:30 Tuesday night. They were lost in deteriorating weather, running low on fuel and needing a vector to the nearest airport. An Air Canada flight, cruising overhead at well over 30,000 feet, picked up their call for help and relayed it to the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC) at CFB Trenton. It was determined that the lost airplane was somewhere north of Haliburton/Stanhope Municipal Airport and deep in the heart of the Algonquin Highlands. JRCC scrambled a Hercules and Griffon helicopter to respond while the Air Canada crew tried to keep the pilot calm. Another aircraft activated the runway lights at Stanhope in the hopes that the lost crew could see them.

They made their last radio call at 9:28pm, almost three and one-half hours after departing Rockcliffe - which lay only an hour and a half's flying to the east.

The accident site was eventually located in a heavily wooded and hilly area about 20 miles north-east of the airport at Stanhope. A Canadian Forces search and rescue technician was lowered into the crash site at 4:30 the next morning - about an hour before I learned of the crash - and confirmed that both pilot and passenger were dead.

By mid morning, I had connected the dots and realized that they were the two guys I had crossed paths with in the clubhouse the evening before.

I have been fortunate in that, thus far, I have been largely untouched by the cruel finality of aviation's ugliest side. I had a few acquaintances die in plane crashes. I think of one fairly often - although I'm not entirely sure why as we didn't know each other very well. I suppose it's because he was very kind to me at a time when I was starting a job in a place that was very intimidating and where I knew few people. While we hadn't spoken in some time, his death affected me deeply. Every so often, I come across a picture or a social media post and I'm taken back to a beach on Lake Ontario. He's standing in the warm light of a giant bonfire fed by pilfered avgas - offering a cold beer with an outstretched hand and a mischievous smile.

The deaths of these two strangers rattled me to my core. Why would anyone embark on that kind of flight, I wondered, with incredulity bordering on fury. A light, single-engine aircraft crossing the dark, featureless, unforgiving expanse of Algonquin Park, at night, in strong winds and deteriorating weather is at best, a bad idea and, at worst, the eventual tragic result. Why didn't I ask where they were going? If they'd told me, I would have suggested staying the night or, if they absolutely had to go, recommended heading south-west to Kingston and then following the illuminated ribbon of Highway 401 to home and safety. Would they have listened? Would it have mattered? I'd flown over the relatively well-populated southern extremities of that area before, in daytime, and was struck by how brutally inhospitable it was.

At any rate, nothing could change the fact that they ended up smashed against a non-descript hillside in the middle of nowhere for no good reason.

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada released some preliminary information about a month later. The agency said the aircraft's propeller struck a 20 foot tall tree about 30 feet back from where the main wreckage came to rest. Investigators found a little more than 6 gallons of fuel in the Cessna's tanks. The photographs suggest the airplane struck the hillside with significant force.

I can't imagine what they went through in those final moments. I hope they had no idea of what lurked in the darkness. A significant part of me hopes they weren't aware of the final link in a chain of extraordinarily poor decisions.

|

| An alternate view of the same Jenny in the same tree. I'd never seen this one before this writing. |

All I could think about was that old poster hanging above the toilet. I couldn't rid my mind of the Jenny and the tree.

A week later, on a chilly morning under searing blue skies, I went for a walk with one of my best friends. We had been colleagues at the station for nearly a decade, coming into the business within months of each other. While our careers followed similar paths, I now found myself behind the camera while he still plied his trade in the public eye. Our friendship grew out of the workplace to include starting a private riot when the Vancouver Canucks let their Stanley Cup slip away, downing a case of beer while doing a terrible job of painting a garage door and depraved bachelor party shenanigans that won't be outlined here. I was godfather to his three sons and he would take that role when our child came into the world.

We walked in silence. Every so often, I looked up at the sky, squinting against the light, and thought it could be worse.

"Well, it was great working with you, brother," John said.

We both knew that we were done. Having come into the television news world together, it was fitting that we would leave it jointly - at least for the moment.

Half an hour later, each of us was read a script. Our network had, through a major restructuring that had become à la mode in recent years, cut some 80 positions. Ours were among them.

Two days before my 31st birthday, less than 3 months before the birth of our first child and for the first time in 15 years, I found myself without work.

No comments:

Post a Comment