Since early this morning, the vindictive sun has burned a searing hole in the late July sky. The air itself is heavy and thick and it seems as though the entire world is burning. If there were even a whisper of wind, it would blow the trees down and scatter their bones across the scorched countryside like dust.

The scene crawling by under twin wings is uniform brown, yellow and gold - a shimmering carpet of desolation. The hills roil and swell like a gritty sea frozen in time. Every few miles, a old farmhouse, barn and broken fence line drift by - abandoned, derelict and cast adrift.

Drawing a deep breath in does little more than sear my insides. I've spent the better part of the day trying to stay awake - mouth agape, eyes staring dumbly and unfocused, sweat dribbling down my forehead - and pleading to get off the ground.

In the cockpit, here aloft, there is little respite from this hell. Even the wind being shoved back from the propeller thrashing against the thin air is insultingly hot.

The sun remains an unflinching, relentlessly pulsating, white hot blotch on the cloudless sky.

The hum of the engine and subtle vibration of my machine is lulling me to sleep. I gasp, taking desperate gulps of air. I hope against hope that they might revive me.

.jpg) |

| Charlie Miller poses for a hero shot before departing on a flight. (Photo courtesy: Charles Miller) |

Still, these solo patrols are a rare joy. There is no leader to guard, no wingman to worry about...or weep over when they fail to return from a raid. It is only I and my airplane and all is as it should be.

Nearly, though. I've noticed a barely perceptible change in the engine's drone. I've felt the change rather than heard or seen it but I know something is amiss. A quick scan of the sparse instrumentation and the mixture knob reveals itself as the most likely culprit. In my heat induced stupor I must have brushed my sleeve against it and drawn it out further than it needs to be. I lean forward to adjust it - happy to perform a commonplace duty that requires some measure of attention.

I feel the bone-jarring hammer blows of the twin Spandau machine gun before I hear them.

I am suddenly very much awake.

The mixture control is quickly forgotten and I instinctively slam the stick one way and push opposite rudder to the floor. The horizon abandons all reason and spins around madly. The sound of the slipsteam changes in tone as the wind strums the flying wires. My stomach turns.

I am looking through a neat, little hole punched in the upper right corner of my windshield. From its borders, tiny, hairlike cracks splay out like beams from today's harsh sun. I've never seen such a perfect circle. I would marvel in its beauty and simplicity if not for the fact that, had I not leaned aside to adjust the mixture, the bullet that created that hole would have buried itself below my right eye.

I jerk my head around. My silk scarf billows out behind me as the flaps from my leather helmet slap my cheeks. Another biplane is turning around below and behind my ship. It has cream coloured wings with red stripes and a crimson nosebowl. I recognise it instantly as the mount belonging to a rival ace.

I push the throttle through the gate and I smoothly pull back and to the left. My biplane slows as we approach inverted and I add enough rudder to bring the nose around. My target is hovering below me now and clawing his way skyward in a climbing turn. I let the nose drop through the inverted and roll hard to the right.

|

| Charlie Miller in FAM (right) on the tail of Gordon Skerratt's CF-REB. (Photo courtesy: Charles Miller) |

The cream and crimson biplane is sitting in the middle of my windscreen now. His wings, however, are set at a sharp angle and it is immediately obvious that he is approaching at a great velocity. I may have but an instant to strike.

I feel the airplane shudder and slow as I fire the Vickers machine guns. The smell of cordite fills the cockpit and dust speckles my goggles. He flashes by over my top wing, engine snarling in defiance. I pull back hard and arc high to the left, tilting my head back to catch a glimpse of my quarry. My skin is on fire with the heat and slick with sweat but my insides are ice cold. The longer this jousting match continues, the greater his odds of winning are. I must end it quickly.

This last maneuver was more aggressive than the one before it and so the target I'm presented with is more profile and therefore, better. I give him another two second burst blast from the Vickers. The result is devastating. Angry tongues of flame lick at his cowls. The engine vomits thick, black smoke tempered with wisps of white and grey. It billows between the wings and wires, obscuring the cockpit.

The handsome little biplane steepens her roll towards me. I pull back on the stick and we're carried above her. I watch her slide underneath and roll onto her back. Then, she dives out of view.

|

| Charlie (right) and Gord (left) in an aerial jousting match. (Photo courtesy: Charles Miller) |

My senses heightened now, my eyes catch a shade of movement on the right wingtip. It is but a dot...but oddly out of place. I roll sharply towards the new target. My airplane responds immediately as if invigorated by this change in office - from hunted to hunter.

Our speed builds and the rush of air around the little ship intensifies to a gale. The dot floating in the middle of my windshield sprouts two wings and a tail. As I continue my approach, it grows larger. I hunch my shoulders and flex my fingers around the control column. I hear my heart thumping in my head.

My target is one of the new monoplanes. He is cruising leisurely...and very much alone. I am so close now that I can easily see where the fabric around the exhaust stacks has darkened with heat and grime. I can can count every rib pushing against the red fabric. There is a name stencilled below the cockpit rim...and a small patch of fabric covering some recent damage. The rigger has yet to paint it to match the rest of the ship.

I trigger the Vickers guns. I hear a metallic clang but no bullets emerge and my prey flies idly on.

Jammed! my mind screams.

I haul back on the stick and we rush upwards. I feel the monoplane slide beneath us. I tilt my head back and see that I've betrayed my approach. He is now very much aware of my presence and is maneuvering to gain the advantage. I roll out to face him and we rush towards each other head on. As his machine swells in my sights, I wonder what, exactly, it is that I'm doing.

I break hard, up and to my left. The horizon tilts crazily and slips out of view and I pull the airplane into a near vertical bank. My opponent flashes by. The muzzles of his twin Spandau twinkle and an instant later I hear and feel his bullets whizzing past. He roars overhead and I yank the stick into my belly and bound upwards to follow.

This deadly dance continues for what seems an eternity but may be, in fact, mere minutes. My new opponent is an old and skilled hand. There are no wasted movements. Each act is calculated and deliberate yet executed so swiftly one gets the impression he isn't thinking at all but running purely on instinct. It becomes evident that the outcome of this meeting will not depend on who is more skilled but rather on who will commit the first error.

That, inevitably, falls to me. I pull too hard in an effort to get on his tail. My biplane, forsaken by her master, wallows right, then snaps her left wing down hard and tumbles into a spin. I react instinctively and she snaps out of the spin as quickly as she fell into it. Still, it is too late. As I pull out of the dive, his bullets are spiralling between the wings and through the flying wires.

My opponent may be faster, more skilled and able to both out-dive and out-climb me but there is scarcely a ship in the skies that can out-turn this biplane.

|

| C-FFAM maneuvering. (Photo courtesy: Charles Miller) |

At intervals, the monoplane's pilot takes pot shots at me. His fire arcs hopelessly wide and falls away. He cannot score a hit without tightening his turn; he is not able to tighten his turn without stalling out.

And so, we've arrived at an impasse. I begin hammering a gloved fist against the jammed Vickers guns.

After a few minutes, on one of my frantic glances rearward, I notice my hunter has disappeared. I level the wings to discover he is flying alongside. He pulls his goggles away from his eyes to reveal a jovial grin on an oil-streaked face. He raises a gauntlet in salute, waggles his wings and starts a sweeping turn to the west.

I watch him for a long while. He floats away until his craft becomes a mere speck and that speck fades into the countryside. I have no concept of time. Was I watching him for a minute? An hour?

I am drawn again to the neat, little hole that turned this lazy, limp, sun stroked afternoon into a sweat soaked nightmare.

Why had I leaned forward at that exact moment?

To adjust the mixture, naturally.

Naturally, I reply. But why not a moment earlier? Or worse, a moment later?

Silence. The engine's mindless hum is my only reply.

And why the mixture? And what if my sleeve hadn't brushed against it in the first place? What if I'd leaned the other way to, say, scratch my shin? Or grab the chart stuffed into my right boot?

What if, what if, what if...

|

| Charlie and FAM doing their best impression of the Red Baron. (Photo courtesy: Charles Miller) |

Now, the sky is rusting. Every colour in the scarlet spectrum is bleeding from the atmosphere; from deep reds the colour of velvet to light yellows that remind me of cornfields in the fall. It is as if a crazed painter, in a fit of rage, has thrown his entire palette at the canvas. I am watching each colour smear itself against the sky, collect in heavy ridges along the silhouetted hillsides and drip onto the earth below.

It's time to go home.

I close the throttle and let the speed spill from the wings. The earth rises up to meet me and I level off just above the countryside. In this fashion, in order to escape detection, I will lurk back to my home field. In short order, I realise this is an exercise in futility. My airplane is painted an emphatic red and white. If my intent is to escape attention, I may as well be on fire.

An ironic smirk touches my lips. I remind myself that I very nearly was - twice.

When I reach my home field, the last of light has bled from sky leaving it an ashen indigo blue. The landing has its usual charm but is otherwise uneventful. I taxi to my tie down and switch off the engine.

All the other airplane are in their spots. I'm the last to return.

Despite the setting sun, it is still very warm and I'm in a hurry to get out of the airplane. I pull off my goggles and damp helmet and hang them on the intersecting flying wires to my left. I run a hand through my dark hair, matted with sweat, and smooth out my moustache. I take a deep breath, wrap my gloved hands around the cabanes and pull.

Nothing. My legs are useless.

Fine, I muse. I'll sit here awhile longer.

Inevitably, my eyes return to the hole. Its creator is lodged in the headrest behind me. I know this without having seen it.

I am wondering if the spider leg cracks are in fact growing before my eyes, when I see, through the hole, two beams of light piercing the gloom. They bob and roll, seemingly at random, as they search the twilight, reaching into the thickening darkness. My ears are still ringing from the sound of the engine but I am sure I hear the whine of a motor in low gear...and the sound linen makes when it tears.

Bunny pulls up in the duty car and bounces to a stop - grinding the gears. He whistles and points to the offending hole.

"Nasty bit, that," he yells over the sound of the motor. "How'd you dodge it?"

I shrug and give him a tired smile.

"Never mind," Bunny says. "Hop in. Beers are on you tonight!"

In a few minutes, we push our way into a crowded tavern. The barman grins and nods toward the far corner where a table is laden with burgers, chips, gravy and pub fare. There are puddles of beer everywhere. Crowded around the table are the other pilots - still clad in leather flying jackets and oil-stained coveralls.

Woven into the din hanging over the bar, I pick out solitary phrases.

"So, there I was, hanging in my straps...and Roy comes up from behind..."

"I swear I had the son of a bitch...and next thing I know, he's on my tail..."

"...out of airspeed, out of ideas and staring God in the face...I thought I was a goner, for sure..."

Bunny muscles his way in and I drop into a chair next to him. My first opponent from this evening is sitting across the table. He slides a large, glistening pint of ale across to me.

"Bottoms up, Charlie," Gordy says. He's a good friend, Gordon Skerratt - perhaps the best. On most days, he's my faithful wingman and I am his. On this day, however, I've flamed him and his Smith Miniplane CF-REB. His airplane is just fine and tied down a short drive away. The bullets, smoke and flame were imaginary. The victory, however, is very real.

|

| Gordy Skerratt in CF-REB. (Photo courtesy: Charles Miller) |

I take a long swig. The beer is cold and slakes my thirst. I loudly proclaim that it is the best beer I've ever had.

"I thought I had you for sure," Gordy says. "How did you get around so quickly?"

"No idea," I shrug. "I hauled back on the stick and then there you were. I must have blacked out."

"Obviously." Gordy says, laughing.

At the other end of the table, George Jones, our local EAA president, is recounting how he came to be Roy Hems' victim on this day. George is excitedly describing the mock dogfight with his hands. Roy, who flew Spitfires in the second world war, is sipping beer and silently saying a prayer of thanks that today's battle was fought with their imaginations rather than with tracer bullets.

A few seats away, George Welsch, another World War II Spitfire pilot, is in conversation with one of the combatants. He's sliding his pint in circles absent-mindedly. Beer sloshes from the stein's mouth and collects on the slick table. Our eyes meet and he gives me the same grin he flashed from the cockpit of his Flybaby not an hour ago. He's the pursuer who let his prey go when my Vickers guns jammed.

I raise my glass in salute. George, his face still dark with oil, returns the gesture.

When I get to the bottom of my first beer, another magically appears before me. The excited chatter continues well into the evening.

|

| The "Brampton Boys" on their way to the Battle of Caledon Hills. (Photo Courtesy: Charles Miller) |

And so it went, once a week, all summer long. Some guys even called in sick to get out to the airport early and stake the best chance to "bounce" an opponent. At a predetermined time, EAA airplanes would meet over the Caledon Hills north of Toronto and every pilot would be on the look out for an attack from any side. There were no guns, obviously, so a "kill" would be scored once the aggressor pilot latched onto an opponent's tail. A head-on attack or a strike from the side would not count.

From the ground, it must been quite a sight: a cloud of colorful airplanes tangling like gnats, buzzing as they looped, rolled, yanked and banked around the summer sky.

It might have been a scene out of France during the Great War or a snapshot of the long-gone era of swashbuckling barnstormers and aerial daredevils. In this era of widespread controlled airspace, highly travelled airways, glass cockpits, urban sprawl and crowded skies, it is hard to imagine such a day ever existed. The truth is, it wasn't that long ago that Miller and his mates were wheeling free above a quilt of farm fields, jockeying for position and glory - for the pure fun of flight. These were carefree days. They revelled in the rush of speed, the exhilaration of the wind's breath rushing through the cockpit and along the fabric flanks, the surreal sensation of gravity's pull and lift's might...the magic of flight.

|

| Charlie Miller and FAM. (Photo courtesy: Charles Miller) |

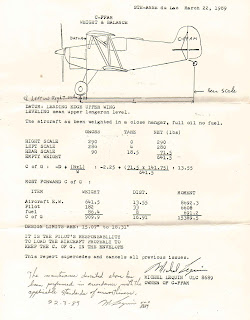

It is a secret not often revealed by the select few who have been tasked with keeping it. Every so often, in rare occasions, it is betrayed in a smile, a glint in an old pilot's eye or a whispered tale. I saw it in the first photograph Charlie sent me of his prized airplane. Miller, clad in an old flight suit, boots, a worn leather helmet, goggles and a pencil thin moustache, is perched in the cockpit - looking over the top wing. Even in black and white, FAM shines brightly - not a blemish on her rosy skin. Miller's eyes are ablaze. His face is frozen in time, a mischievous half-smile formed on his lips...as if he's in the middle of teasing whoever is behind the lens.

If you look closely, you might just see it.